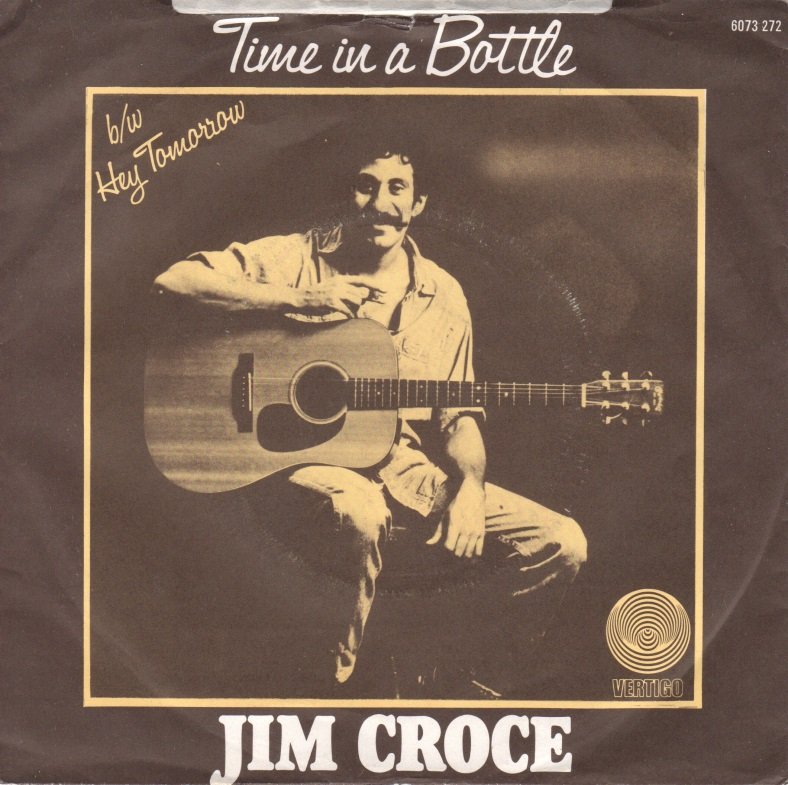

Few songs arrive like a quiet confession and then refuse to leave the room. Jim Croce’s “Time in a Bottle” did exactly that—an unassuming acoustic piece that turned into a living memory, carried in house radios, weddings and hospital rooms for generations.

Carved from the gentle sound of a single guitar and a whisper of piano, the song belongs to that rare group of recordings that sound older and younger at once: old because of its timeless sorrow, young because its wish—to freeze a perfect moment—remains fresh. On the album You Don’t Mess Around with Jim, the track sits like a private letter, offered to anyone who will listen.

Croce’s guitar work is the song’s heartbeat. His fingerpicking is spare but exact, setting a slow, reflective pace. A soft piano line and a touch of harpsichord lift the melody into a space that feels almost sacred, as if time itself were being measured in small, careful notes. The arrangement avoids drama; it insists instead on intimacy.

The lyrics are plain and devastating. They speak of saving days and holding on to love—an idea that proved heartbreakingly resonant when fate and loss touched Croce’s life soon after the song found its widest audience. That context gave the song an extra edge, turning a love song into something like a premonition.

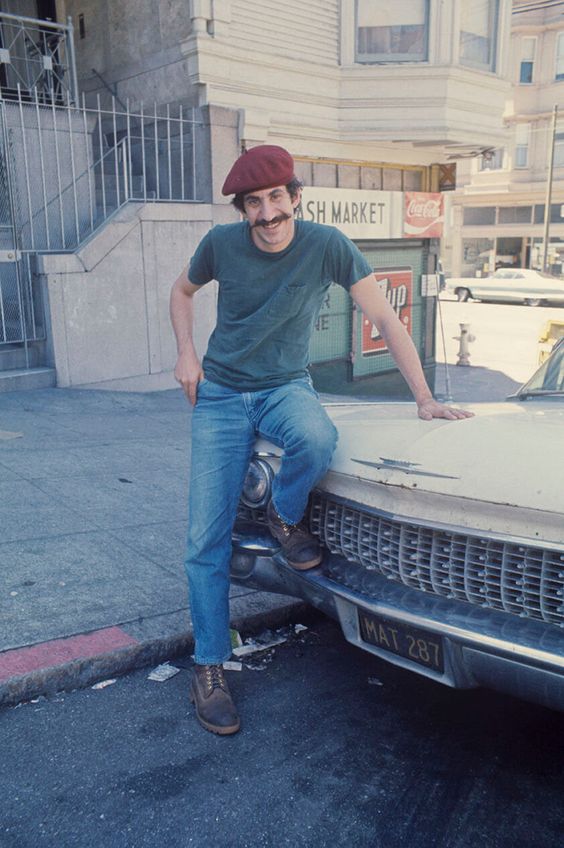

“He always wrote like he was talking to you across the kitchen table,” said Ingrid Croce, Jim Croce’s wife and longtime manager, recalling the way the songwriter treated small moments as if they were everything. Ingrid Croce, wife and manager.

That simple, domestic image—songwriter as confidant—helps explain why the song crossed age and genre barriers. It is used in homes and hospitals, in quiet corners and public ceremonies. For listeners in their fifties and beyond, the song often functions as a map of memory: a sound that will pull you back to a single night, a single person.

Music scholars point to the unusual blend of instruments as a key to the song’s staying power. The harpsichord, uncommon in folk ballads, gives the track an almost classical patience. The near-absence of percussion leaves room for the voice to do the work: to carry longing, regret and a steady, careful hope.

“The recording refuses to clutter itself,” said Dr. Helen Murray, musicologist and author on American songcraft. “It clears space so the listener can place themselves inside the lyric.” Dr. Helen Murray, musicologist.

These elements combine to make the song useful in a way few pop hits are. It is a first-dance song, a farewell hymn, a private prayer. It is also, in a strange way, a study in restraint. At a time when radio favored big production and louder statements, Croce’s piece was a quiet counterargument: emotion need not be loud to be lasting.

The album that held it mixed upbeat storytelling with slow, inward moments—Croce’s range was broad—but “Time in a Bottle” became the singular, fragile jewel. Audiences found in it a language for the impossible wish to keep time itself. Musicians who followed borrowed its lesson: simplicity can be precise, and honesty can be the device that makes a song eternal.

Listeners who grew up with AM dials and vinyl singles still put it on when they need a familiar voice. Newer listeners discover it on streaming playlists and in movie soundtracks, surprised that a two-minute song can carry so much gravity. The tune’s endurance is part craft and part tender accident, a meeting of careful songwriting and life’s sudden turns that left the song hovering, luminous—