Jim Reeves took a hymn born of raw grief and made it feel like a hand on your shoulder — steady, warm, and quietly commanding. His velvet baritone turned Thomas A. Dorsey’s plea for guidance into a personal prayer that still comforts people who remember, mourn, and long for peace.

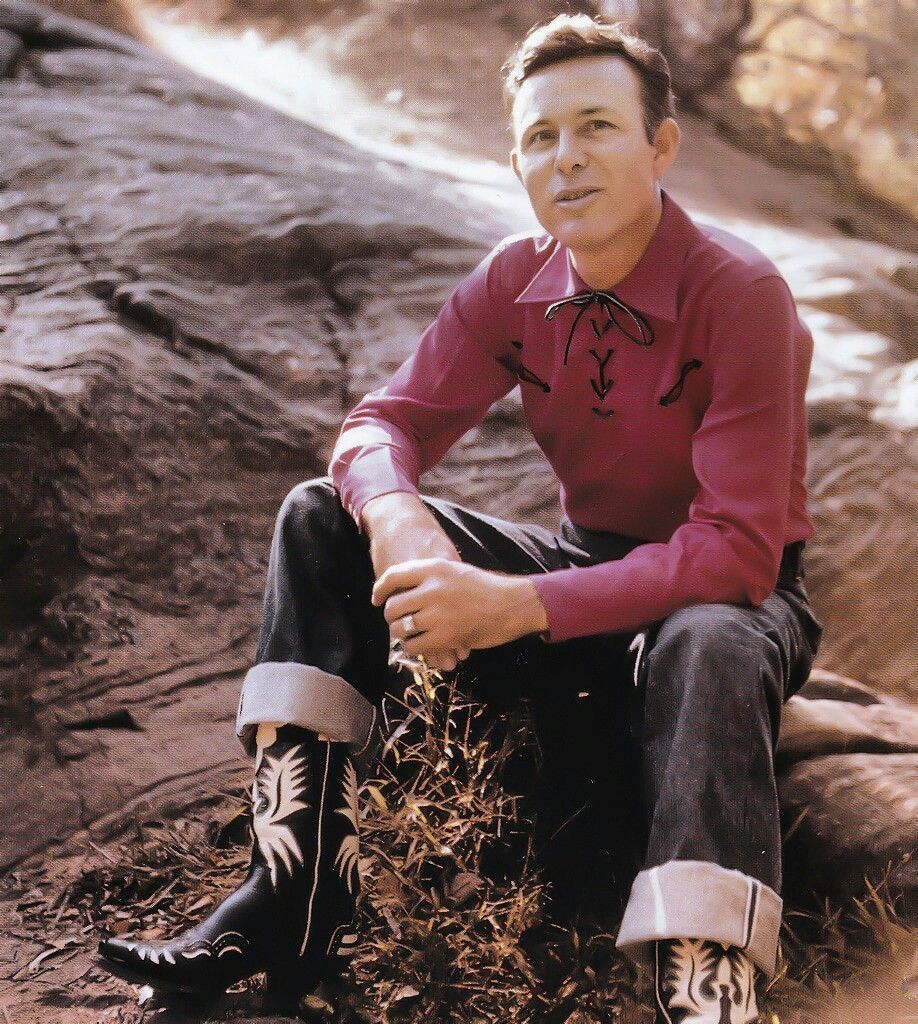

The song itself grew from unimaginable sorrow. Thomas A. Dorsey wrote “Take My Hand, Precious Lord” after losing his wife and newborn son, pouring a lifetime of faith and pain into simple, direct lines that ask for guidance through darkness. Reeves, known to many as “Gentleman Jim,” approached the hymn not as a showpiece but as a confession. He sang like a man who had listened to the world’s troubles and wanted to offer rest.

Reeves’ recording is spare where some versions swell. The arrangement lets his baritone carry the weight; his phrasing slows at the right moments so each line lands like a small ceremony. For older listeners who grew up with Reeves on the radio or in the church hall, his rendition is more than nostalgia. It is a familiar presence in lonely rooms and at kitchen tables when grief arrives without warning.

“Jim Reeves didn’t perform this song — he delivered it. His voice made the listener feel attended to, as if someone was guiding them through a storm,” Dr. Emily Carter, Professor of Music History at Vanderbilt University

The plainness of the lyrics is part of the song’s power. Lines such as “lead me on, let me stand” are not grand theology; they are an honest request for help. Reeves’ tone, controlled and reverent, frames that request as both humble and unshakable. It is easy to imagine congregations and families leaning in, mouths half-open, letting the words settle.

Reeves’ faith was not a stage accessory. He recorded gospel songs throughout his career and made them part of his public identity. Even after his untimely death in a plane crash, his music found its way into moments of private sorrow and public memorial. Churches still play his version; families still choose it at wakes and quiet gatherings.

“Whenever the world felt too loud, people told me they put on Jim Reeves’ hymn and sat very still. They said it felt like a familiar hand,” Mary Lawson, longtime church organist and community music leader

The hymn’s reach goes beyond denominational lines. Its themes — weariness, hope, surrender — are universal. That universality allowed Reeves to bridge audiences who might otherwise not cross musical lines: country fans, gospel congregations, and older listeners who preferred a voice they could trust. For many, his rendition became the version they came to know as the definitive one.

There are technical reasons for the recording’s enduring effect. Reeves’ diction is clear; he neither rushes nor decorates. The accompaniment is unobtrusive, a cushion rather than a show. This restraint gives the song room to breathe, and it gives the listener room to feel. The result is an intimacy that older adults often describe as healing rather than merely enjoyable.

The stories attached to the song matter almost as much as the sound. Listeners recall funerals and hospital visits, quiet afternoons on the porch, or the hush of a living room when grief came to call. In those stories, Reeves’ voice is a constant — a sonic anchor when memory and loss were otherwise unmoored.

As generations pass, recordings can dull. But when a song is as straightforward and human as “Take My Hand, Precious Lord,” and when it is sung with the kind of steadiness Jim Reeves brought, that recording keeps renewing itself. It returns in small rituals, in community sings, and in the gentle silence after the last line is sung, when the listener still holds on to the image of a guiding hand —