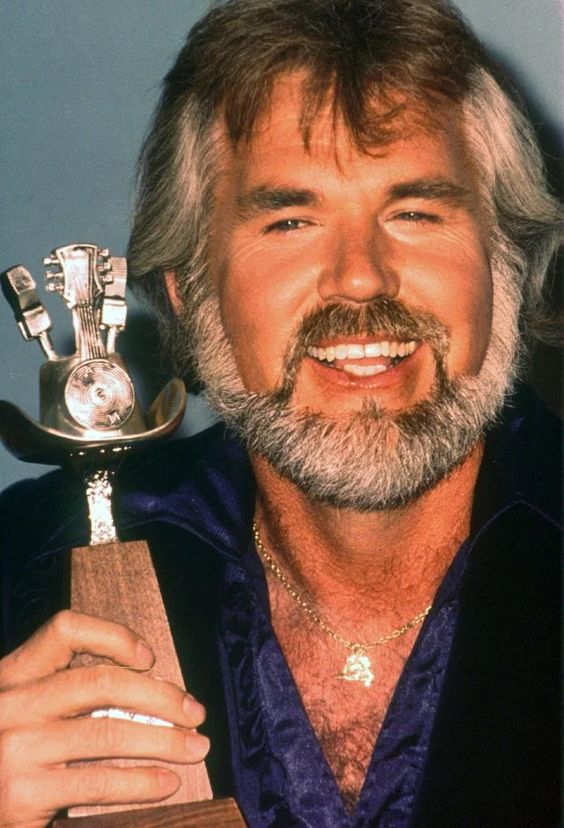

Kenny Rogers’ “If I Ever Fall in Love Again” reads like a quiet confession from a man who has learned to guard his heart — and yet can’t entirely close it. The slow, aching ballad, recorded for the album Something Inside So Strong, pairs Rogers’ warm baritone with the delicate touch of a duet partner to explore the wary yearning of someone who has loved and been hurt.

On the surface it is a simple country ballad. Underneath, it is a study in careful feeling. Rogers opens with a voice that admits its scars and asks what it would take to love again. The song’s arrangement is modest: a piano sets the reflective tone, strings melt in to soften the edges, and a patient tempo allows every phrase to land. The result is not showy; it is intimate, like a conversation between two people past their first mistakes and trying to be honest.

Listeners who remember radio in the late 1980s recall the song as a duet staple, often paired with Anne Murray. Together, their voices create a balance — his weathered warmth meeting her crystalline steadiness — that makes the emotional give-and-take feel real. The lyrics do not grandstand. They catalog conditions: trust, patience, and the slow rebuilding of courage. For older listeners, the song lands differently than flashier hits; it asks for time and reflection rather than fireworks.

Anne Murray, country singer, says the duet was “about two people trying to protect what’s left of their hearts while daring to believe in something better.”

That tension — the line between hope and fear — is the song’s engine. Rogers does not promise a tidy answer. Instead, he lays out a cautious wish: a longing for companionship that will not repeat old pain. The instrumentation mirrors this restraint. Piano and soft percussion keep the drive calm; strings warm the chords as if to suggest a cautious thaw.

Contemporary critics noted the song’s appeal to listeners who had lived through divorce, loss, and the slow rebuilding that follows. It was not meant to be a wedding song, or a declaration of all-conquering romance. It was an honest admission that love can return only on new terms. That practical honesty made it a quiet comfort for fans who preferred songs that spoke to real, later-life concerns.

Dr. Elaine Rivers, musicologist and author, observes: “Songs like this reach a different part of the listener. They aren’t about falling head-over-heels; they’re about learning how to stand beside someone again.”

The recording sits in Rogers’ catalog as a moment of reflective tenderness, not a commercial peak. Yet its legacy is in how it gave permission to feel both guarded and open. For many listeners, especially older adults, the song became a companion for slow evenings and thoughtful afternoons — a reminder that longing can coexist with caution.

Behind the scenes, the choice to keep the arrangement restrained was deliberate. Producers leaned into Rogers’ gift for storytelling through tone rather than theatrics. The result is a track that rewards close listening: small inflections, a held breath before a line, a brief swell in the strings — all signals of emotional life lived rather than imagined.

In households where the record shaped playlists for company and solitude alike, the song worked quietly. It did not demand attention; it invited it. And in that invitation lies its power: a confession about love that is both fragile and stubbornly hopeful — a voice saying, cautiously, that the heart might open again.