In a simple, aching melody, a generation learned to remember. Mary Hopkin’s “Those Were the Days” rose from a BBC discovery to become a quiet, unstoppable anthem of longing — a song whose strings and voice have kept pulling at listeners’ memories for decades.

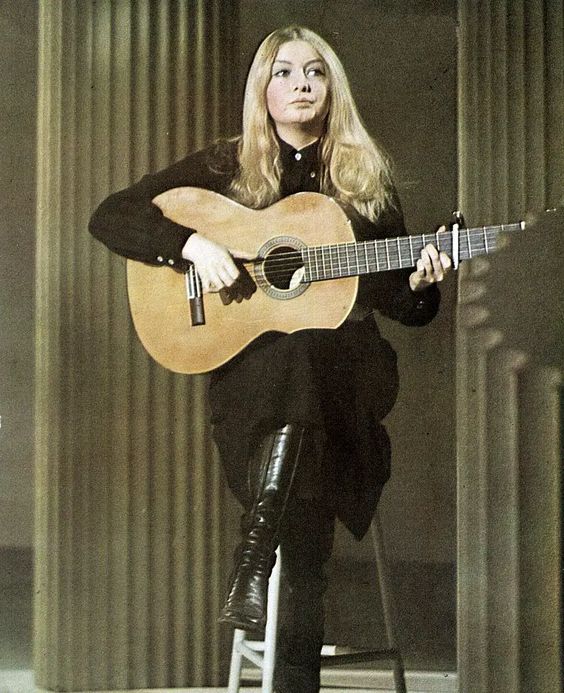

Hopkin’s recording, cut for her debut album Postcard and shepherded by Beatle Paul McCartney, married folk simplicity to orchestral sweep. The result felt old and new at once: an Eastern-European folk tune reimagined with lush strings, piano and a spare acoustic guitar. For many listeners who grew up in the era, the song became shorthand for a time that felt both golden and gone.

Hopkin’s voice is the instrument that makes the comeback real. She sings as if recalling a life she once lived, not inventing it. Critics and fans point to that mixture of vulnerability and clarity as the song’s power. Paul McCartney’s production choices — where the strings swell but never drown the vocal, where piano and guitar share a soft, steady pulse — gave the piece dignity without excess.

Mary Hopkin, singer: “I never thought the song would hold people’s hearts like this. When I sing it, I see faces and little moments — that is all I ever wanted.”

The song’s lyrics, often quoted and easily hummed, tap into a shared ache. “Those were the days, my friend, we thought they’d never end” is not just a refrain; it is a communal memory. Radio programmers found the song simple to place and hard to forget. It rose on charts across the world and became the single that defined Hopkin’s early career.

Paul McCartney, producer: “We wanted the record to sound warm and human. The arrangement had to lift Mary’s voice while keeping the truth of the song intact.”

Musical detail matters. The opening strings give an immediate sweep of drama. A modest acoustic guitar provides the pulse. The piano sits under the melody like a steady reminder. These choices turned a regional folk theme into a pop standard without robbing it of its melancholic heart. The orchestral touches recall the broad sound of the late 1960s while keeping the focus on Hopkin’s clear delivery.

Music historian Dr. Emma Clarke, who has written about post‑war folk revival, says the song bridged worlds.

Dr. Emma Clarke, music historian: “It carried an old-world tune into the clean studio sheen of pop radio. That bridge is why people of all ages found it so immediate.”

For listeners aged 50 and over, the track functions as both time capsule and mirror. It conjures first loves, village dances, small triumphs and private losses. Its continued use in films and television has kept it in public earshot, and Hopkin’s occasional live performances bring a new set of listeners to an old refrain.

Numbers matter, but the truth is felt in living rooms and at kitchen tables. The song’s chart success in many countries is a headline; the deeper story is how a compact arrangement and an unadorned vocal shaped a global memory. McCartney’s stewardship and Hopkin’s performance created a recording that sounds like a story told by someone you trust.

The cultural ripple is clear: cover versions, soundtrack placements and steady radio play have kept the song afloat in public memory. For those who lived through the era, it is a portal. For younger listeners, it remains an evocative puzzle — a piece of music that asks them to imagine simpler scenes and then